KEO News Wire

ESL: Views from a “fan of the future”

Adam Walton reflects on the short lived proposition of the European Super League (ESL), and Florentino Perez’s complete oversight of the sentiments and importance of soccer’s global fanbase and community.

Amongst the dredge of articles and tweets churned up by Sunday’s announcement and subsequent collapse of the European Super League, BBC reporter Dan Roan revealed how elite-club bigwigs were justifying their coup. Roan tweeted, ‘According to source, some of those involved in ESL call traditional supporters of clubs “legacy fans” while they are focused instead on the “fans of the future” who want superstar names’.

These sentiments were echoed by Super League chairman, Florentino Perez, on Spanish television, who claimed, ‘Young people are no longer interested in football. They have other platforms on which to distract themselves.’ Basically, Perez and his cronies don’t care about local fans, because the real money comes from the streams and shirt sales in places like Delhi and Hong Kong.

After I wiped the tears (of laughter and sadness) from my eyes at the thought of a group of billionaires, who would remember the moon landing, determining the interests of younger generations, I came to a minor realisation. I am a Cape Town-based Arsenal fan in my early-20s whose attention and subscription fees are wanted by these relics. The European Super League was created for me. Wow.

This supposed fan-dichotomy relates to a question brilliantly tackled by Jonathan Wilson on The Guardian Football Weekly: is a local fan’s connection superior to the fan who lives 60 000kms away? Do these groups want different things?

I have no familial connection to Arsenal. I don’t have an uncle who played for their youth team in the mid-1980s. I wasn’t bought a shirt with “Henry” printed on the back for my fifth birthday. I would have to drive 13 144,6km on the Trans-Sahara Highway to get from my front door to the Emirates Stadium. Yet I have missed only two Arsenal games this season, and I was furious when I did. My family still talks about a tantrum I threw when the Gunners lost 3-2 to Swansea in 2012. And during the depths of lockdown, when I (like most people) was struggling with the seeming hopelessness of everything, just watching my team play was a soothing two-hour escape from bleak circumstance.

This isn’t a shrine to my footballing loyalty. There are far more moving stories of “foreign” fandom: people waking up at ungodly hours to watch 0-0 draws with Crystal Palace; tattoos of club crests on unmentionable places; life-savings spent on trips to watch favourite teams play. Yes, these fans may not live within walking distance from Old Trafford, but to question their connection to the club is ludicrous.

So where does this connection come from? Of course, there’s an appreciation for the sport itself. But beyond this, there is the inseparable feeling that a community is sitting and watching your team with you. When Harry Kane scores a last-minute winner, a fan in their living room celebrates knowing thousands of like-minded people, who share a passion for a football club and it values, are celebrating with them. It’s a shared emotional experience. Subconscious maybe, but palpably important.

A geographically-challenged fan is also not confined to their living room. I have had multiple conversations in bars with complete strangers about whether Diogo Jota should play instead of Roberto Firmino, or about how Brendan Rodgers gets his teeth whitened. Beyond supporting a club, there is the experience of being a footballing fan, of being part of a community.

This is the answer to Wilson’s question. The experience of a fan in Brasilia might be different from the fan in Manchester. But both value that intangible feeling of connection, in whatever form it comes. It’s what makes someone who has never stepped foot in England cry when a football club in South London win a game. It’s what makes being a fan so fulfilling, and its non-negotiable.

KEO News Wire

Stormers lead the SA charge in Investec Champions Cup play-off race

John Dobson’s Stormers have played themselves into contention to host a play-off in the Investec Champions Cup. The top eight teams, from the competing 24, play at home in the last 16, which will happen in April in 2026.

The Stormers are one of just six teams unbeaten after the opening two-round block of Europe’s most prestigious club rugby competition.

They lead Pool 3 on points differential from Irish club giants Leinster, who have won the title four times. Leinster are also unbeaten.

With each title comes the sought after star, and France’s Toulouse, with six stars in the 30 year competition history, tells you just how difficult it is to win the Champions Cup.

Last season’s finalists, Bordeaux and Northampton Saints, were drawn in the same Pool this season and both are unbeaten and lead the overall standings with the maximum league points and the best points differential.

Bristol’s Bears, also in Pool 4 with Bordeaux and the Saints, are also unbeaten and France Smith’s Glasgow Warriors are two from two after their stunning 28-21 home win against Toulouse. The latter led 21-0 at halftime.

Glasgow’s win is among the greatest in Pool stage history.

INVESTEC CHAMPIONS CUP 2025/26 LEAGUE AFTER 2 ROUNDS

- Saints – 10 league points, plus 53 points differential

- Bordeaux – 10 league points, plus 42 differential

- Warriors – 10 league points, plus 12 differential

- Bristol – 9 league points, plus 50 points differential

- Stormers – 9 league points, plus 30 points differential

- Leinster – 9 league points, plus 25 points differential

- Harlequins – 6 league points, plus 37 points differential

- Saracens – 6 league points, plus 32 points differenetial

- Toulouse – 6 league points, plus 30 points differential

- Sale Sharks – 6 league points, plus 16 points differential

- Bath – 6 league points, plus 15 points differential

- Castres – 5 league points, plus 13 points differential

- Munster – 5 league points, plus 2 points differential

- La Rochelle – 5 league points, minus 2 points differential

- Toulon – 5 league points, minus 2 points differential

- Gloucester – 5 league points, minus 8 points differential

- Edinburgh – 5 league points, minus 20 points differential

- Sharks (SA) – 5 league points, minus 32 points differential

- Scarlets – 1 league point, minus 30 points differenetial

- Bulls – 1 league point, minus 58 points differential

- Leicester – 0 league points, minus 27 points differential

- Clermont – 0 league points, minus 58 points differential

- Pau – 0 league points, minus 59 points differential

- Bayonne – 0 league points, minus 63 points differential

The teams all return to the Prem, Top 14 and URC respectively for the next three weeks, before the Investec Champions Cup Round stages are completed on the weekends of the 9th, 10th and 11th & 16t h, 17th & 18th January.

The play-off dates, with home teams determined by their points tally, and then points differential:

-

Last 16 – 03/04/05 April 2026.

-

Quarter-finals – 10/11/12 April 2026.

-

Semi-finals – 01/02/03 May 2026

- Finas – Bilbao – 22/23/ May 2026

KEO News Wire

De Villiers among the elite in Investec Champions Cup

Stormers flanker Paul de Villiers has the joint most turnovers after the completed first block of this season’s Investec Champions Cup, with the opening fortnight of the competition and the EPCR Challenge Cup breaking records for viewership. De Villiers is among five nominations for Player of the Month.

Bulls supporters may not yet have an appreciation of the status of the Investec Champions Cup, with just 7300 attending the opener at Loftus against the 2024/25 champions Bordeaux, but elsewhere the tournament continues to command interest, at the grounds and through television, online and social media viewership.

The Stormers, having played their first competition ‘home’ game outside of Cape Town due to the unavailability of the DHL Stadium, still got a crowd of 17 000 for their win against La Rochelle, while plenty tuned into the Sharks home win against Saracens, even if awful weather conditions limited ground attendance.

The Keo & Zels show, on their social media channels, combined for a viewership of 1.2 million, whilst SA Rugby Magazine published 130 articles on the tournament in the past three weeks, and 230 social media posts across their platforms, as well as their WhatsApp Channel & the Keo & Zels WhatsApp Channel.

The EPCR reported that Broadcast audiences also surged, with peak TV viewership exceeding 2 million on France Télévisions for the RC Toulon v Bath Rugby clash, reinforcing the competitions’ status as must-watch sporting event.

Digital engagement also continued its upward trajectory year on year, demonstrated by 3.65 million total digital engagements, up from 2.75 million at the same stage last season, and 3 million YouTube highlight views, a 25% increase on last season.

The EPCR also launched a brand-new Investec Champions Cup show, produced by Brian O’Driscoll and Craig Doyle’s 3 Rock production company and fronted by former French international Ben Kayser, celebrating the cities, culture and fans of the Investec Champions Cup – as well as the world-class Test match rugby in club colours.

Bordeaux’s French International flyhalf Matthieu Jalibert has won Investec Player of the Match in both Bordeaux’s wins, Stormers flyhalf Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu joined the list of players with the second most try assists in one match (4), with Toulouse and France No 9 Antoine Dupont’s 5 setting the standard.

Toulouse’s Jack Willis, the Top 14 and French rugby player of the year last season, has been imposing in this year’s opening two rounds, and, in the 21-28 defeat to Glasgow, made 25 tackles. Willis is ineligible for England selection because he plays his club rugby in France.

Toulouse’s Thomas Ramos has also thrived, at flyhalf in Round 1 and fullback in Round 2.

Across 42 high-quality matches in Rounds 1 and 2 of the Investec Champions Cup and EPCR Challenge Cup, Europe and South Africa’s leading clubs and players delivered compelling performances that set the tone for the rest of the campaign.

That exceptional standard of play is reflected in the Investec Champions Cup Player of the Month nominees, each of whom led by example and played a key role in guiding their teams to consecutive victories.

- Adam Hastings, Glasgow Warriors. Investec Player of the Match against Stade Toulousain during Glasgow’s unbelievable comeback in Round 2.

- George Hendy, Northampton Saints. Scored four tries in 2 Rounds and was Investec Player of the Match against Vodacom Bulls in Round 2.

- Paul de Villiers, DHL Stormers. Investec Player of the Match against Stade Rochelais in Round 2 and joint most turnovers so far in the competition.

- Matthieu Jalibert, Union Bordeaux Bègles. More points than any other player (28) thanks to three tries, five conversions and a penalty goal in two Rounds. Was the Player of the Match in both matches.

- Sione Tuipulotu, Glasgow Warriors. Hugely influential in Glasgow’s historic win against Stade Toulousain and one of the seasons’ top carriers.

Just six of the 24 teams are unbeaten in the opening fortnight.

In Pool 1, Franco Smith’s Glasgow are the only unbeaten team, with two wins from two. The quality and fight within the Pool is illustrated with with one league point separating second place Saracens (6) and fifth placed Sharks, from KZN, who have five points after the bonus-point home win against Saracens.

There is no unbeaten team in Pool 2, with Bath toping the table.

In Pool three, the Cape Town based Stormers are unbeaten and edge Leinster at the top of the table on points differential. Both teams have nine league points.

Last season’s finalists, Bordeaux and Northampton Saints were drawn in Pool 4, and the Saints are on top on points differential, with Bordeaux second and the unbeaten Bristol Bears third.

SPRINGBOKS STAND TALLEST FOR SOUTH AFRICA IN INVESTEC CHAMPIONS CUP

*Explaining the EPCR

European Professional Club Rugby (EPCR) is the organiser of the Investec Champions Cup and EPCR Challenge Cup. EPCR’s mission is to create outstanding rugby experiences for all key stakeholders, including leagues, clubs, players, match officials, unions, fans, broadcast and commercial partners, communities and the media.

The Investec Champions Cup and EPCR Challenge Cup feature clubs from the Gallagher Premiership, TOP 14 and United Rugby Championship. 42 clubs from three leagues and eight unions compete each season to win club rugby’s most elite titles. Broadcast to over 100 territories around the world, last season EPCR’s tournaments welcomed 1.5 million fans into stadia and achieved a broadcast audience of over 70 million viewers.

The EPCR Finals Weekend is a destination rugby weekend held in a different city every year.

On 22 and 23 May 2026, the vibrant Basque city of Bilbao will welcome the EPCR Challenge Cup Final and Investec Champions Cup Final to the stunning San Mamés Stadium, where 60% of tickets for the Bilbao Finals already sold,

Established in 2014 with headquarters in Lausanne, Switzerland, EPCR has the following members: Fédération Française de Rugby (FFR), Federazione Italiana Rugby (FIR), Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU), Ligue Nationale de Rugby (LNR), Premier Rugby Ltd (PRL), PRO Rugby Championship DAC (URC), Rugby Football Union (RFU), Scottish Rugby Union (SRU) and Welsh Rugby Union (WRU).

The Board of EPCR has the following members: Dominic McKay (Chairman), Jacques Raynaud (EPCR CEO), Martin Anayi (URC), Emmanuel Eschalier (LNR), Simon Massie-Taylor (PRL), Mark McCafferty (independent director), Arnaud Nourry (independent director), Jérémie Lecha (FFR) and Kevin Potts (IRFU).

EPCR’s revenues are distributed on the basis of an equal three-way division to Premiership Rugby clubs, URC clubs and LNR clubs.

EPCR’s tournaments are run according to World Rugby’s Laws of the Game, and to World Rugby Regulations.

LinkedIn page: www.linkedin.com/company/

EPCR contact: [email protected]

KEO News Wire

Dylan Maart nominated for Investec Champions Cup Try of the Round

Stormers winger Dylan Maart is among the Investec Champions Cup Round 2 Try of the Round nominees. Give him your support South Africa.

Maart scored a brace of tries in the Stormers’ 42-21 Investec Champions Cup win over La Rochelle in Gqeberha on Saturday.

REPORT: Stormers subdue spirited La Rochelle

At 29, when many players are well-established in their careers, Maart made a life-altering decision to leave his job as a warehouse worker at a bottling plant and betting everything on rugby.

Two years later, that gamble has taken him from the fringes of South African rugby to the Currie Cup podium, the Vodacom URC stage and the bright lights of the Champions Cup with the Stormers.

“I played rugby in primary school, but nothing in high school, for various reasons,” Maart told Rapport. “Things weren’t good at home. There were many nights when there was no food and we went to sleep hungry.”

At just 13, he worked as a taxi guard – opening doors, collecting fares, carrying bags – simply to help put food on the table. It was also the only way he could get to school in Paarl, riding for free because he worked on the taxi.

But Maart never let go of his love for the game.

When his chance finally came, he grabbed it with both hands, winning promotion and silverware with the Boland Cavaliers, becoming a cornerstone of a Griquas side that ended a 55-year Currie Cup drought, and now making his mark in Stormers colours following a loan deal.

The Stormers are two from two in the Investec Champions Cup and have put themselves in a position to host a last 16 home play-off and more home play-offs because of their excellent start.

The Stormers, in 2025/26 are eight wins from eight starts in all competitions, with just two of those wins coming at their home venue, the DHL Stadium in Cape Town.

They play the Lions in their final match of the year in Cape Town at the DHL Stadium on Saturday. It is in the URC in what will be their ninth match of the 2025/26 season.

SUPER SATURDAY FOR STORMERS AND SHARKS

KEO News Wire

In-form Springboks trio star in the Investec Champions Cup

The in-form Springboks trio wearing numbers 9, 10 and 12 of November continued their hot form in Round 2 of the Investec Champions Cup.

Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu (Stormers), Andre Esterhuizen (Sharks) and Cobus Reinach (Stormers) were South Africa’s biggest individual contributors. Their match statistics reinforced their contributions.

Bulls No 8 Elrigh Louw, in his comeback month, was comfortably his team’s best performer.

Feinberg-Mngomezulu’s individual statistics against La Rochelle read like a distinction list, with Paul de Villiers and Cobus Reinach producing massive individual returns in the 42-21 Investec Champions Cup win against La Rochelle.

Feinberg-Mngomezulu made the most metres (90), beat the most defenders (7), made the most kicks in play (11) and carried the ball the most (13). Player of the Match De Villiers, who won vital turnovers on his team’s own try line, made the most tackles (16), beat four defenders, the second most among the Stormers, alongside scrum half Cobus Reinach, and made the fifth most running metres (47). He also was made the third most carries (9), one behind second placed Reinach.

The impact of Springboks Reinach and Feinberg-Mngomezulu is emphasised by their individual contributions and collective as a halfback pairing. The duo featured as the biggest contributors in every one of the four primary attacking categories.

De Villiers’s all-round impact, on attack, defensively and at the breakdown speaks to his Investec Player of the Match Award.

SUPER SATURDAY FOR STORMERS AND SHARKS

Sharks inside centre captain Andre Esterhuizen, in his 100th match for the Sharks, made the most tackles for his team (14), the most carries (11), beat the most defenders (5) and made the second most metres (29). His fellow Springboks midfielder beat four defenders, which was the second most for the Sharks.

EVERY PLAYER STATISTIC AND TEAM STATISTIC FROM ROUND 2s 12 MATCHES

Springbok loose-forward Elrigh Louw, in his first start of the season after a lengthy lay-off because of a serious leg injury, was the top performer for the embattled Bulls against the Northampton Saints. The Bulls lost 50-5 but Louw was the the only bright light on a dark night.

Louw, who started at No 8, played for 58 minutes in his third comeback match. He made the most carry metres, 41, the second most tackles (13), which was one less than Marcell Coetzee and he won the most turnovers for the Bulls (2).

KEO News Wire

Stormers and Sharks deliver as Bulls take heavy hit in Investec Champions Cup Round 2

Round 2 of the Investec Champions Cup delivered big results, with South African teams at the heart of the weekend’s action. The Stormers and Sharks both notched morale-boosting wins, while the Bulls endured a punishing afternoon in Northampton.

The Stormers opened Saturday’s fixtures with a commanding 42–21 win over defending champions Stade Rochelais in Cape Town. Physical dominance up front and clinical finishing saw the hosts pull away in the second half to maintain their perfect start to the tournament.

Over in Durban, the Sharks showed resilience to edge Saracens 28–23 in wet conditions at Kings Park. The hosts held off a late surge from the English giants to claim their first win of the campaign.

But it was a difficult outing for the Bulls, who travelled to face Northampton Saints and were outplayed in all areas. The 52–5 defeat was compounded by a hat-trick from Saints winger George Hendy, who now has four tries in the tournament.

South African-born Ernst van Rhyn featured again for Sale Sharks, who ran in five tries in a 35–14 victory over Clermont in France. Sale’s backline sliced through with ease as they claimed a valuable away win.

Elsewhere, Leinster held off a strong challenge from Leicester Tigers on Friday night to win 23–15, while Glasgow Warriors pulled off the shock of the round recovering from 21–0 down to beat Stade Toulousain 28–21.

Bordeaux Bègles racked up 50 points against Scarlets, and Munster turned on the style late to beat Gloucester 31–3.

Sunday’s action saw Harlequins dismantle Bayonne 68–14, Castres blank Edinburgh 33–0, and Toulon edge Bath 45–34 in a high-scoring thriller. Bristol Bears closed out the round with a dominant 61–12 win over Pau.

Investec Champions Cup Round 2 Results

Friday

-

Leicester Tigers 15–23 Leinster Rugby

Saturday

-

DHL Stormers 42–21 Stade Rochelais

-

Hollywoodbets Sharks 28–23 Saracens

-

ASM Clermont Auvergne 14–35 Sale Sharks

-

Union Bordeaux Bègles 50–21 Scarlets

-

Munster Rugby 31–3 Gloucester Rugby

-

Glasgow Warriors 28–21 Stade Toulousain

Sunday

-

Harlequins 68–14 Aviron Bayonnais

-

Castres Olympique 33–0 Edinburgh Rugby

-

RC Toulon 45–34 Bath Rugby

-

Northampton Saints 52–5 Vodacom Bulls

-

Bristol Bears 61–12 Section Paloise

KEO News Wire

Cheetahs, Lions fall short as EPCR Challenge Cup brings late drama

South Africa’s two representatives in the EPCR Challenge Cup both suffered Round 2 defeats on Saturday, as European sides produced a mix of dominance and drama across the competition.

The Cheetahs started brightly in Amsterdam, leading Stade Français at the break, but were overwhelmed in the second half. The French club ran in six tries including a brace for Thibaut Motassi to clinch a convincing 45–22 bonus-point win.

In Newcastle, the Lions looked set to bounce back from their opening loss after an early try from Angelo Davids. But the Red Bulls held firm and struck late, with a 78th-minute Murray McCallum try snatching a 14–10 victory for the hosts.

Elsewhere, Benetton backed up their Round 1 result with a 44–31 home win over USAP, while Ospreys overcame a spirited Montauban side 33–22 despite a second-half wobble.

In Galway, Connacht were ruthless in a 52–0 demolition of Black Lion, with Paul Boyle grabbing a first-half hat-trick. In contrast, Cardiff edged Ulster 29–26 in a thriller, with Callum Sheedy’s late penalty sealing the win after a dramatic fightback from the Welsh side.

Sunday delivered more excitement as Racing 92 salvaged a 31–31 draw with Exeter Chiefs thanks to an 83rd-minute conversion by Geronimo Prisciantelli. Meanwhile, Dragons RFC snapped a year-long losing streak with a 23–21 comeback win over Lyon.

EPCR Challenge Cup Round 2 Results

Saturday:

-

Benetton Rugby 44–31 USAP

-

Toyota Cheetahs 22–45 Stade Français

-

US Montauban 22–33 Ospreys

-

Newcastle Red Bulls 14–10 Lions

-

Connacht Rugby 52–0 Black Lion

-

Cardiff Rugby 29–26 Ulster Rugby

Sunday:

-

Racing 92 31–31 Exeter Chiefs

-

Dragons RFC 23–21 Lyon Olympique

KEO News Wire

Elrigh Louw brings light to another dark day for belittled Bulls

Springbok Elrigh Louw was the light for the Bulls on what was another dark day in the 2025/26 season, writes Mark Keohane.

The Bulls were belittled, more than beaten, by the Northampton Saints on Sunday in the Investec Champions Cup, and what made the afternoon that much more embarrassing for the South Africans is that the Saints were not at their best for the first 50 minutes.

Louw, who played more minutes against the Saints than he has since coming back for a serious injury and nearly a year out of the sport, is growing in confidence and strength. The Springboks No 8 is a class act and he was the one player who looked like an international in a Bulls match 23 that played with little intensity and even less regard for the preciousness of holding onto the ball.

Louw, who started at No 8, played for 58 minutes in his third comeback match. He made the most carry metres, 41, the second most tackles (13), which was one less than Marcell Coetzee and he won the most turnovers for the Bulls (2).

Unfortunately, on this particular afternoon Kade Wolhuter produced probably his worst match of a young professional career. Wolhuter, 24, was a schoolboy star for Paul Roos, Western Province and South Africa’s Youth Teams, but he has battled to transition to professional rugby, having moved from Western Province and the Stormers to the Lions and now the Bulls.

He missed his only two kicks at posts and, as a team and coach killer, he missed three penalty kicks to the touchline. All of these misses were punished by the Saints on the counter-attack. His skill set deserted him with each passing minute and his chip kicks were poor, his passes were ineffective or intercepted and the worse it got, the further back in the pocket he stood.

Springboks two-times World Cup winner and flyhalf Handre Pollard’s presence would have made a difference to the performance but it would not have changed the result.

The Bulls have problems, are devoid of confidence, seem confused as to how to play and most certainly are not showing the desire to prove to new coach Johann Ackerman that the squad should remain the same next season.

Their Investec Champions Cup campaign is over before 2026 has started, having lost both matches in December and conceded 96 points in the process. Their URC campaign is not looking healthy, with three wins in six starts.

The Saints, winners at Pau, are well positioned going into the new year, and they will back themselves to host a home last 16 play-off match.

The Investec Champions Cup, in the play-offs is a representation of the toughest club competition in the world, but the league stages need a revisit, as does the schedule, because too many teams are sending lambs to the slaughter in away games, and then backing big home wins to make the play-offs.

There are six clubs, at best, with proper depth to compete in their domestic competition in parallel to the Investec Champions Cup, and even a club like Saracens found out that to win in South Africa, like in France, you have to send your best squad. They will be hurt by the defeat to the Sharks in Durban.

The Bulls, somehow, trailed 7-5 after 35 minutes and had so many opportunities to be ahead and to put doubt into the home team players and supporters, but the ill-discipline and lack of defensive structure, intensity or mongrel, resulted in a 50-5 defeat.

It got messy in the end and it is going to continue to get messy for the Bulls if they fail to address the fact that they have a serious defensive problem.

READ ALL THE LATEST FROM THE INVESTEC CHAMPIONS CUP

KEO News Wire

SA’s Super Saturday as Stormers & Sharks win big

The Investec Champions Cup play-off ambition lives strong for the Stormers and Sharks after contrasting, but equally decisive wins on Saturday, writes Mark Keohane.

The Stormers and Sharks both made a statement to teams from up north. Bring your best squads to the Republic to beat South Africa’s elite. Defending champions Bordeaux recognised this a week ago when they went to Pretoria and downed the Bulls. They picked their strongest available match 23, including 16 internationals.

A lessor squad would not have come back from 33-22 at halftime but the world class squad of Bordeaux won comfortably 46-33.

La Rochelle, a two-time title winner, played kids against the Stormers and got done with more ease than the scoreboard suggests.

The Stormers scored six tries to three and had two disallowed in the first 15 minutes. They could – and should – have been 24-0 up before the 15th minute. They played with pace and width and Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu’s line kicking was a lesson in accuracy and control.

Inside of him, Springboks scrum half Cobus Reinach played as if he had spent the past decade at the Stormers. Reinach, on signing for the Stormers from Montpellier, made it clear he was not moving to the Stormers to wind down his career. He was moving to win matches and titles.

The Stormers won 42-21 and felt they should have done better. Their coaches lamented periods of the game, in which they lost shape, structure and the ball.

But they scored at will, when they needed to, and defended with purpose when it was demanded to keep out the youthful La Rochelle set-up.

Flanker Paul de Villiers were brutal over the ball, winning crucial turnovers and the Stormers pack, as a collective, never seemed troubled. De Villiers was named Investec Player of the Match, and Feinberg-Mngomezulu and Reinach were as imposing in their individual brilliance and clutch moments.

La Rochelle’s coaching team spoke of the gains from a young squad, how they felt they matched the Stormers for physicality but were undone by the initial pace at which the Stormers played.

The Stormers captain Salmaan Moerat, when told of this, said it had been noted, especially the view that they had expected more physicality from the Stormers.

The Stormers are two from two in the Investec Champions Cup, with an away win at Bayonne in France a week ago, and now this win at the Nelson Mandela Bay Stadium.

They are also six from six in the Vodacom United Rugby Championship, having not played at their home base in Cape Town since the league’s opening two matches in the last week week of September and first week in October.

They’ve done the next six on the road, in five different countries, with and without their current Springboks.

They play the Lions in the URC on Saturday in Cape Town, but for now the relief was the opening fortnight of the Investec Champions Cup had been safely negotiated and the Stormers sit atop of their Pool, edging Leinster on points difference.

WATCH: STORMERS WIN FOR 8th SUCCESSIVE TIME IN ALL COMPETITIONS

KEO & ZELS CALLED THE STORMERS AND SHARKS INVESTEC CHAMPIONS CUP WINS

INPHO/Steve Haag Sports

JP Pietersen’s tenure as Sharks coach got reward as the hosts beat Saracens 28-23 in Durban.

The weather conditions were tough, the match was tough, and not easy on the eye, but the Sharks played with desire to get a result after a woeful start to the competition and an equally poor start to the URC.

Saracens rested some of their biggest names in Owen Farrell, Jamie George and Maro Entoje, and the Sharks were the beneficiaries of this marvellous England trio not being in the match 23.

Andre Esterhuizen, at inside centre, played his 100th match for the Sharks and led the team as captain.

Springboks captain Siya Kolisi started and emptied the tank in his 51 minute performance. Kolisi scored the opening try in a match that could have gone either way. Saracens had a chance to draw/win the match with the last play in injury time, but they knocked on a metre from the Sharks try line and the victory belonged to the Sharks.

*In the EPCR Challenge Cup, RedBull Newcastle scored in the 78th minute to beat South Africa’s Lions 14-10 and Stade Francis beat the Cheetahs 45-22 in Amsterdam.

For all the latest on the SA challenge in the Investec Champions Cup, visit SARugbymag

KEO News Wire

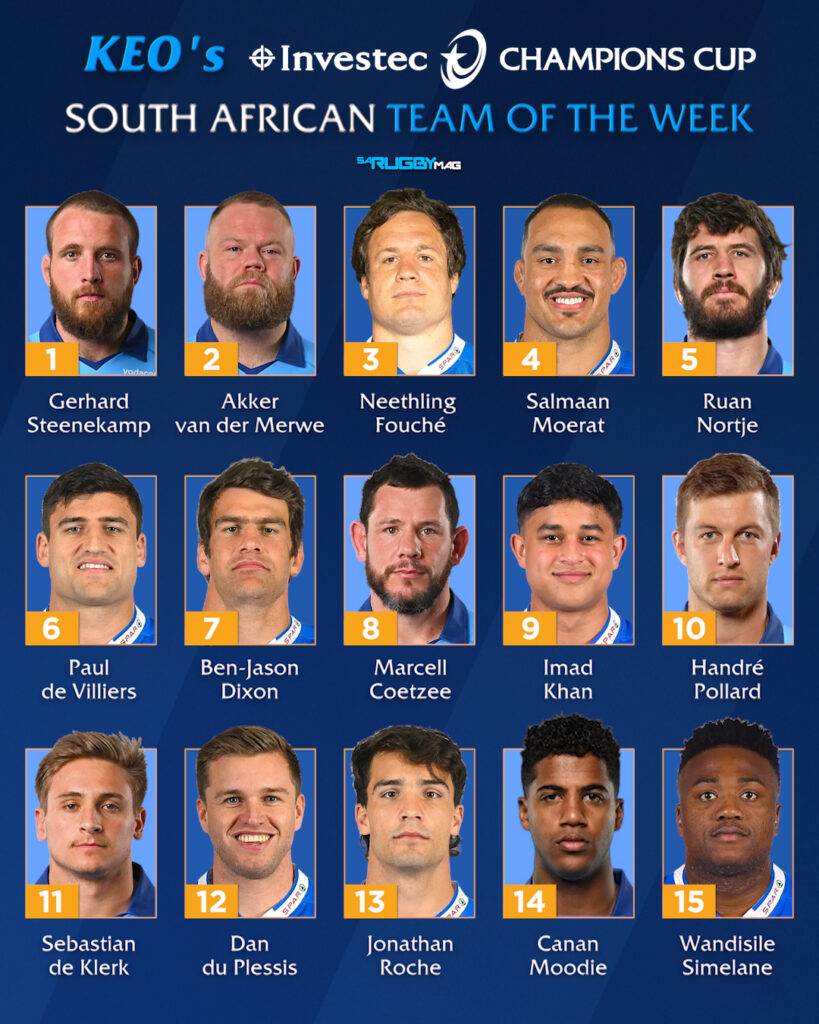

SA stars crack Investec Champions Cup Team of the Week

Three players from South African franchises have been included in the Investec Champions Cup Team of the Week following standout performances in Round 1.

Stormers front-rower Ntuthuko Mchunu was rewarded for a powerful display at loosehead, while his teammate Ben-Jason Dixon earned selection at flank after a high work-rate showing against Bayonne.

Sebastian de Klerk, the Vodacom Bulls speedster, claimed the left wing jersey after crossing the tryline in the Bulls’ thrilling clash with Bordeaux.

Also featuring in the XV is Kyle Steyn, the Glasgow Warriors captain, who qualifies via his South African roots and filled the right wing spot after a strong outing against Sale Sharks.

Selections were based on performance data from Oval Insights.

Keo selected his SA Team of the Week, that consist of 8 Stormers and 7 Bulls players. Sadly, no Sharks player made the cut.

KEO News Wire

Investec Champions Cup running red hot in Round 2

The Stormers and La Rochelle will be the weekend’s headline act in South Africa in Round 2 of the Investec Champions Cup.

English giants Saracens travel to Durban to play the Sharks and the Bulls are away to last season’s beaten finalists, Northampton Saints.

Home wins are non-negotiable for potential title winners and while the Stormers won’t exactly be playing at home in Cape Town, they will be in South Africa for their showdown with French club La Rochelle.

The Stormers won’t play in Cape Town because the stadium is unavailable this weekend, but they will play Leicester’s Tigers at the DHL Stadium in Cape Town in their final Pool match mid-January, 2026.

Stormers vs La Rochelle

Nelson Mandela Bay Stadium

Fresh from an impressive away win over Bayonne, the Stormers return to home soil to face a powerful Rochelle outfit. Flyhalf Clinton Swart led all point-scorers in Round 1 with 16, and the Cape side were excellent at the breakdown, winning more turnovers than any other team (10). Swart also leads the tournament in kick metres with 415.

La Rochelle were equally dominant in their opener, scoring six tries and controlling the maul. Hooker Tolu Latu hit 13/13 lineouts, while Oscar Jegou crossed twice. This is a clash of breakdown steel versus French physicality .

Expect plenty of changes to the match 23s that featured in last weekend’s opening round, where the Stormers and La Rochelle both won.

ROUND 1’s BIG GUNS FIRED BIG SHOTS

Sharks vs Saracens

Hollywoodbets Kings Park

The Sharks will be desperate to respond after leaking eight tries to Toulouse. Despite the loss, they topped the round for offloads (18) and dominant carry contacts (32), with Batho Hlekani and Le-Roux Malan both physical threats. They’ll need to tighten up defensively against a clinical Saracens side who beat Clermont 47–10.

Teenage wing sensation Noah Caluori was sharp in Round 1 with 116 metres gained and seven defenders beaten, while Nick Tompkins delivered five offloads in a typically slick Saracens performance .

Bulls vs Northampton Saints

Franklin’s Gardens

The Bulls showed attacking promise in a five-try effort against Bordeaux but ultimately fell short at home. Defence will be key against a Saints team that won their opener and brings a sharp mix of pace and structure. The Bulls will need more discipline and accuracy to make an impact in Pool 4.

Ernst van Rhyn (Sale Sharks) vs Clermont

Ernst van Rhyn delivered a defensive masterclass in Round 1, making a tournament-high 31 tackles for Sale in their narrow loss to Glasgow. He’ll be key again as the English club faces a Clermont side reeling from a heavy defeat to Saracens .

AFRICA PICKS: WHO CASHED IN ON THE OPENING WEEKEND

Also in Round 2

-

Leicester vs Leicester – Jordan Larmour (171m, 7 defenders beaten) leads a Leinster side that looked sharp in attack.

-

Toulouse vs Glasgow – The French giants ran in eight tries last week. Ange Capuozzo scored a hat-trick.

-

Munster vs Gloucester – Both sides are chasing consistency after mixed Round 1 showings.

KEO News Wire

It’s win or bust for Lions & Cheetahs in the EPCR

The Lions and Cheetahs must win in Round 2 of the EPCR Challenge Cup if they are to have any play-off aspirations. Both South African teams lost their opening round matches.

Lions vs Newcastle Red Bulls

Kingston Park

The Lions led 18-11 against Benetton in Johannesburg with nine minutes to play and lost 26-18.

Their attacking stats were among the best, leading the tournament in offloads (20) and kick metres (991). Ruan Venter was a standout with seven dominant carry contacts, while Erich Cronje and Quan Horn created problems with ball in hand.

Newcastle showed set-piece control and strong kicking structure in their opening win, away from home, in Lyon, with George McGuigan commanding the lineouts and Amanaki Mafi making 20 carries .

Cheetahs vs Stade Français

NRCA Stadium

The Cheetahs struggled against Exeter, conceding six tries, but there were positives. Michael Annies made 107 running metres and beat six defenders, while flanker Gideon van der Merwe led the competition round with five turnovers. They’ll face a Stade Français side that fired six tries past Cardiff and looked sharp across the park.

Lester Etien and Louis Foursans-Bourdette led the Parisians’ attack, combining for big metres, try assists, and line breaks .

The Cheetahs play their home matches out of the Netherlands and are based in Amsterdam for the EPCR.

Also in Round 2

-

Ulster vs Cardiff – Ulster’s nine-try demolition of Racing 92 puts them top of Pool 3.

-

Benetton vs USAP – Two strong starters go head-to-head after confident Round 1 wins.

-

Montpellier vs Zebre – Montpellier led in post-contact metres, while Zebre were clinical in defence and goal-kicking.

-

Ospreys vs Montauban – Ospreys boast the tournament’s best tackle success rate and strong breakdown control.

KEO News Wire

South African stars shine bright in Champions Cup opener

South African players made a major impact in the opening round of the Investec Champions Cup, with Clinton Swart and Ernst van Rhyn delivering standout performances despite mixed results for their teams.

Swart Steers Stormers to Victory

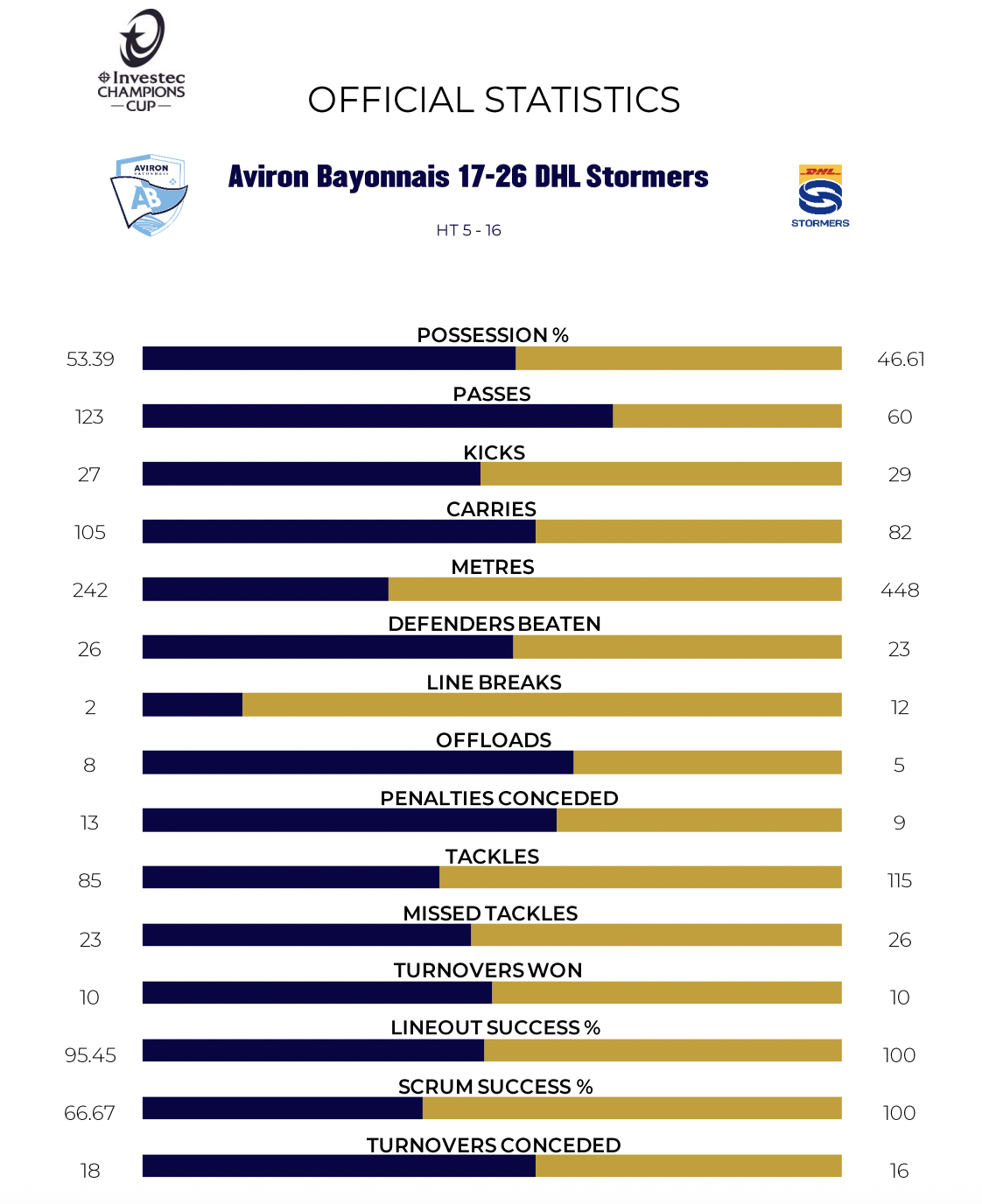

On loan from the Pumas, Clinton Swart made an immediate impression on debut for the Stormers. The flyhalf was instrumental in their 26-17 away win over Bayonne, contributing 16 points through four penalties and two conversions. Swart finished the weekend as the tournament’s top point-scorer, leading the charts across all 12 matches.

Van Rhyn’s Defensive Heroics

Former Stormers lock and current Sale Sharks flank Ernst van Rhyn put in a massive shift on defence, making a tournament-high 31 tackles during his side’s narrow 26-21 defeat to Glasgow Warriors in Manchester. His relentless work rate was a bright spot in an otherwise frustrating result for the English side.

Mixed Weekend for SA Teams

While the Stormers secured a gritty win, other South African franchises struggled. The Sharks were outclassed by Toulouse, who ran in eight tries in a dominant performance. Meanwhile, the Bulls fell just short against defending champions Bordeaux, who overturned a 10-point halftime deficit to earn a rare away win at Loftus Versfeld.

Bath, Bordeaux and Stormers fire big shots in Investec Champions Cup

Top South African Performers – Round 1

-

Points Leader: Clinton Swart (Stormers) – 16

-

Tackles Leader: Ernst van Rhyn (Sale Sharks) – 31

Round 1 Standouts (All Teams)

-

Carries: Grégory Alldritt (La Rochelle) – 20

-

Metres Gained: Josh McKay (Glasgow) – 121

-

Defenders Beaten: Jordan Larmour (Leinster) – 7

-

Offloads: Gavin Coombes (Munster) – 5

-

Tries: Ange Capuozzo (Toulouse) – 3

Despite a tough round for most South African sides, Swart and Van Rhyn’s individual brilliance shows the depth and quality of SA talent on the European stage.

KEO News Wire

Bath, Bordeaux and Stormers fire big shots in Investec Champions Cup

Johann van Graan’s Bath, the Stormers and defending champions Bordeaux made big statements in the opening round of this season’s Investec Champions Cup.

viron Bayonnais and Sale Sharks had the honour of hosting Round 1’s openers on Friday night when they welcomed DHL Stormers and Glasgow Warriors respectively.

Despite unwavering passion, Stade Jean-Dauger’s invincibility finally tumbled for the first time this season. South Africa’s DHL Stormers showed they meant business in Bayonne when Imad Khan went over two minutes into his debut start.

Saturday brought with it a Saracens lesson as they swiped aside ASM Clermont Auvergne, before Union Bordeaux Bègles got their title defence off the perfect start in South Africa.

The reigning champions scored 24 unanswered points in the second half against Vodacom Bulls to complete an historic comeback – they were the first French side to win away at the Bulls’ ring.

Brilliant Bordeaux bulldoze bewildered Bulls

Stade Rochelais and Leinster Rugby both got the better of Leicester Tigers and Harlequins respectively before Bristol Bears had to dig deep to overcome Scarlets by one point.

Closing out Saturday’s action was a masterclass from Bath Rugby. Last season’s EPCR Challenge Cup winners, Bath more than proved why many have them as favourites this year when they flew into a four-try, 18-minute lead at The Rec.

It ended 40-14 to the English side as they look to next week’s trip to RC Toulon.

Finalists Northampton Saints were forced to leave it late by valiant newbies Section Paloise before Stade Toulousain showcased their potential against Hollywoodbets Sharks.

La Rochelle brace for red-hot Stormers in PE

Eight tries, including three for Ange Capuozzo, more than sufficed for Ugo Mola’s men as they out-classed the Sharks 56-19. Oh, and a certain Antoin Dupont made his return to Investec Champions Cup action.

Gloucester Rugby-Castres Olympique and Edinburgh Rugby-RC Toulon closed out a memorable Round 1.

International Rugby

Brilliant Bordeaux bulldoze bewildered Bulls

Bordeaux arrived at Loftus as reigning Investec Champions Cup winners and played like a side intent on keeping the crown. The French giants dismantled a disjointed Bulls outfit 46-33, producing a display that was composed, ruthless and dripping with international class, writes Mark Keohane.

And yes – the Bulls somehow led 33-22 at halftime.

The hosts scored five tries in 40 minutes yet never looked in control. The scoreboard offered false comfort and little else.

Bordeaux’s rhythm, tempo and accuracy suggested they were always the side dictating the contest, even when chasing the game.

Bordeaux travelled with 16 internationals in their match-day squad and their stars delivered. With Maxime Lucu and Matthieu Jalibert running the game like seasoned Test generals, and with Damian Penaud and Louis Bielle-Biarrey finishing with the brutality expected of world-class wings, the Pretoria crowd saw the gulf between elite European champions and a South African side still searching for cohesion.

It was breathless early on.

Bordeaux were seven points clear inside three minutes. The Bulls replied, faltered, struck back again, conceded again, and then surged with three late first-half tries. It looked dramatic on paper, but on the field the French were calmer, more accurate and operating with a clarity the Bulls could not match.

Jalibert toyed with the defence, his footwork and timing repeatedly opening space for a slick midfield. Bielle-Biarrey crossed twice, Penaud added to his outrageous tournament tally, and Bordeaux’s pack kept supplying clean, quick ball.

Once the second half kicked off, the Bulls vanished as an attacking threat. The champions tightened their grip, erased the deficit, and moved into a commanding lead with the kind of composure that wins knockout matches.

The Bulls had chances to claw it back to a single-score game, but their basics imploded. A crucial line-out was lost, the scrum wobbled, and the handling in the backline betrayed panic rather than purpose. Bordeaux, on the counter, could easily have added more.

This was a thorough reminder of what a title-winning squad looks like. Seven tries, four conversions and a penalty told the story.

Handré Pollard was solid early, kicked four from five, but a yellow card and two poor decisions shifted momentum the wrong way. De Klerk and Moodie worked tirelessly on the wings, and the loose trio put in the hard metres, but collectively the Bulls were outclassed.

And the biggest red flag: defence.

It hasn’t been good in the URC and it was worse here. Too many missed one-on-one tackles. Too little scramble. Too little structure. Bordeaux didn’t so much pick locks as walk through open doors.

With just 7,300 supporters turning up, the Bulls needed to deliver something worthy of their faithful. Instead, they teased with ten minutes of excellence and followed it with forty minutes of confusion and concession.

Bordeaux left Pretoria looking every bit a team chasing consecutive European titles. The Bulls left with more questions than answers, too few of them comforting.

Scorers

Bulls

Tries: Sebastian de Klerk, Reinhardt Ludwig, Akker van der Merwe, Canan Moodie, Jeandré Rudolph

Conversions: Handré Pollard (4)

Bordeaux

Tries: Damian Penaud, Louis Bielle-Biarrey (2), Maxime Lamothe, Boris Palu, Matthieu Jalibert, Salesi Rayasi

Conversions: Jalibert (3), Maxime Lucu

Penalty: Jalibert

BULLS – 15 Willie le Roux, 14 Canan Moodie, 13 David Kriel, 12 Harold Vorster, 11 Sebastian de Klerk, 10 Handré Pollard, 9 Paul de Wet, 8 Marcell Coetzee (c), 7 Reinhardt Ludwig, 6 Marco van Staden, 5 JF van Heerden, 4 Cobus Wiese, 3 Mornay Smith, 2 Akker van der Merwe, 1 Alulutho Tshakweni.

Bench: 16 Johann Grobbelaar, 17 Gerhard Steenekamp, 18 Wilco Louw, 19 Ruan Nortje, 20 Elrigh Louw, 21 Jeandré Rudolph, 22 Embrose Papier, 23 Stravino Jacobs.

BORDEAUX BÈGLES – 15 Romain Buros, 14 Damian Penaud, 13 Nicolas Depoortere, 12 Yoram Moefana, 11 Louis Bielle-Biarrey, 10 Matthieu Jalibert, 9 Maxime Lucu (c), 8 Temo Matiu, 7 Cameron Woki, 6 Bastien Vergnes-Taillefer, 5 Adam Coleman, 4 Boris Palu, 3 Carlü Sadie, 2 Maxime Lamothe, 1 Jefferson Poirot.

Bench: 16 Gaetan Barlot, 17 Matis Perchaud, 18 Ben Tameifuna, 19 Jonny Gray, 20 Tiaan Jacobs, 21 Arthur Retiere, 22 Rohan Janse van Rensburg, 23 Salesi Rayasi.

International Rugby

Super Stormers dream of Investec Champions Cup glory

John Dobson’s super Stormers are starting to dream of Investec Champions Cup glory after a stunning away win against Bayonne in France in the 2025/26 season’s opening round.

The Stormers won 26-17, despite being a player down for the final half hour.

Dobson was thrilled with the win, coming a week after a history-making first win the URC against Munster in Limerick, Ireland.

The Stormers, who are six from six in the URC, return to South Africa to play another French giant, La Rochelle next weekend. It won’t be in Cape Town as the DHL Stadium is not available and the match will be played at the Nelson Mandela Bay Stadium in Gqeberha.

Dobson mixed and matched for the Bayonne showdown, but pre-match insisted he had picked a match 23 good enough and talented enough to win against Bayonne, who had lost just once at home in the 2024/25 season in all competitions.

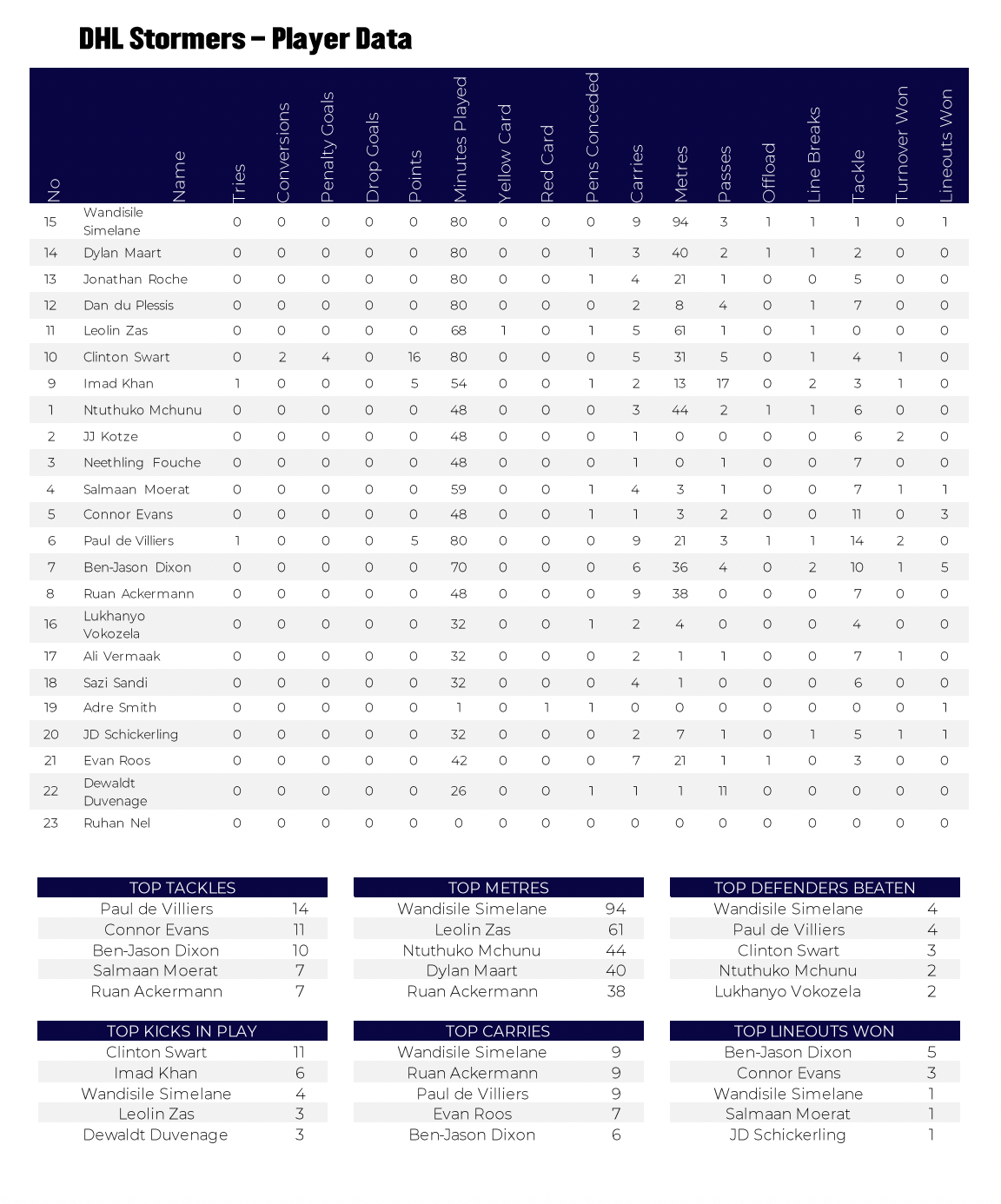

Dobson entrusted the talented 21 year-old scrum half Imad Khan to start and the former Bishops pupil and SA Schools star produced a Player of the Match performance. Loose-forward Paul de Villiers, the former SA under 20 captain, was against outstanding, having been the Player of the Match in Limerick a week ago.

WATCH: MATCH HIGHLIGHTS OF THE STORMERS WIN V BAYONNE

Several of the Stormers backs are not regular starting options, which makes the win that much more impressive, but Dobson said it was a credit to the depth within the squad that results like the one in Bayonne are possible without the likes of Springboks Damian Willemse, Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu, Cobus Reinach and Warrick Gelant, with the backline quartet not in action in Bayonne.

The Stormers made twelve line breaks to Bayonne’s two, but will lament not being more accurate in their finishing.

SA TEAMS CHASE THEIR FIRST STAR

Loose-forwards De Villiers (14 tackles), BJ Dixon (10) and Ruan Ackermann (7) were strong defensively and lock Connor Evans made 11 tackles. Dixon secured five line out takes, the most for the Stormers, and De Villiers’ all-round contribution was impressive, winning two turnovers, one offload, a line break, nine carries, and 21 metres on attack. He also beat four defenders, as did fullback Simelane.

Dixon (70 minutes), Ackermann (48) and Roos (42), were strong in their carries.

AFRICA PICKS: PICK THE STORMERS TO WIN

Clinton Swart, in his first start at flyhalf kicked two conversions and four penalties for 16 points, while fullback Wandisile Simelane made the most attacking metres (94).

The Stormers line out return was 100 percent.

Bayonne:

Tries: Mori, Erbinartagaray, Paulos

Con: Segonds

DHL Stormers:

Tries: Khan, De Villiers

Cons: Swart 2

Pens: Swart 4

DHL Stormers: 15 Wandisile Simelane, 14 Dylan Maart, 13 Jonathan Roche, 12 Dan du Plessis, 11 Leolin Zas, 10 Clinton Swart, 9 Imad Khan, 8 Ruan Ackermann, 7 Ben-Jason Dixon, 6 Paul de Villiers, 5 Connor Evans, 4 Salmaan Moerat (captain), 3 Neethling Fouché, 2 JJ Kotzé, 1 Ntuthuko Mchunu.

Replacements: 16 Lukhanyo Vokozela, 17 Ali Vermaak, 18 Sazi Sandi, 19 Adré Smith, 20 JD Schickerling, 21 Evan Roos, 22 Dewaldt Duvenage, 23 Ruhan Nel.

BREAKDOWN OF ALL STORMERS AND BAYONNE”S PLAYER AND TEAM STATISTICS

International Rugby

Investec Champions Cup: Bulls back their Boks to bully Bordeaux

The Bulls are backing their Boks to bully champions Bordeaux of France in this weekend’s opening round of the Investec Champions Cup, writes Mark Keohane.

Every Bulls player on tour with the Springboks in November will be involved as the Bulls look to maker a statement performance against last season’s champions.

Bordeaux and the Bulls played each other at Loftus in the 2024 Pool Stages, with the Bulls winning a 12-try thriller 46-40. Both teams scored six tries two seasons ago and the difference ultimately proved two penalty kicks.

Handre Pollard, the king of kickers, returns to Loftus for his first start in the Champions Cup in the colours of the Bulls. Pollard’s previous Champions Cup history had been with French club Montpellier and English club Leicester.

Pollard will be significant to any Bulls challenge in the greatest club competition in the world, but it is the potency of a power bench that will be the determining factor in this match.

The starting front row from the Springboks 73-0 against Wales in Cardiff a week ago, are on the bench in Gerhard Steenekamp, Johann Grobbelaar and Wilco Louw. Ruan Nortje, the Boks form lock, is among the replacements, as are Elrigh Louw and Embrose Papier, who have played for the Springboks.

AFRICA PICKS: HOW TO CASH IN ON BULLS, SHARKS AND STORMERS

Louw will start his first match in a year after a lengthy spell out of the game because of injury.

Springboks flyer Canan Moodie links up with Springboks Test Centurion Willie le Roux in a back three complimented by the talents of winger Sebastian de Klerk and current Bok Marco van Staaden joins former Bok Marcelle Coetzee in the back row.

There are 13 Springboks in the match 23, with eight of them part of the Springboks 2025 squads. That includes Elrigh Louw, who was picked in the initial squads but did not play because of injury rehabilitation.

WATCH: KEO & ZELS ON THE BULLS, STORMERS AND SHARKS

The Stormers have also mixed and matched for their opening round at Bayonne, where the hosts only home defeat last season was to the Bulls in the Champions Cup.

Boks back superstars Sacha Feinberg-Mngomezulu, Damian Willemse and Cobus Reinach were not considered for the match, given their heavy workloads for the Stormers and Boks over the past two months, but Boks flanker BJ Dixon will play.

The Sharks, who play six-times champions Toulouse, are without several of their current Boks, but will still field a match 23 with international experience.

It is unlikely to be enough to prevent a one-side beating, given the Sharks struggles all season in the URC.

BORDEAUX BÈGLES – 15 Romain Buros, 14 Damian Penaud, 13 Nicolas Depoortere, 12 Yoram Moefana, 11 Louis Bielle-Biarrey, 10 Matthieu Jalibert, 9 Maxime Lucu (c), 8 Temo Matiu, 7 Cameron Woki, 6 Bastien Vergnes-Taillefer, 5 Adam Coleman, 4 Boris Palu, 3 Carlü Sadie, 2 Maxime Lamothe, 1 Jefferson Poirot.

Bench: 16 Gaetan Barlot, 17 Matis Perchaud, 18 Ben Tameifuna, 19 Jonny Gray, 20 Tiaan Jacobs, 21 Arthur Retiere, 22 Rohan Janse van Rensburg, 23 Salesi Rayasi.

SOUTH AFRICA’S INVESTEC CHAMPIONS CUP TRIO CHASE THEIR FIRST STAR

-

KEO News Wire1 day ago

KEO News Wire1 day agoStormers lead the SA charge in Investec Champions Cup play-off race

-

KEO News Wire4 days ago

KEO News Wire4 days agoSA’s Super Saturday as Stormers & Sharks win big

-

KEO News Wire3 days ago

KEO News Wire3 days agoIn-form Springboks trio star in the Investec Champions Cup

-

KEO News Wire3 days ago

KEO News Wire3 days agoElrigh Louw brings light to another dark day for belittled Bulls

-

KEO News Wire3 days ago

KEO News Wire3 days agoStormers and Sharks deliver as Bulls take heavy hit in Investec Champions Cup Round 2

-

KEO News Wire3 days ago

KEO News Wire3 days agoCheetahs, Lions fall short as EPCR Challenge Cup brings late drama

-

KEO News Wire1 day ago

KEO News Wire1 day agoDylan Maart nominated for Investec Champions Cup Try of the Round

-

KEO News Wire1 day ago

KEO News Wire1 day agoDe Villiers among the elite in Investec Champions Cup